It has been a rainy, grey, windy week here, but have I got something that’ll brighten your day! Today’s featured researcher may be off in Finland (along with her dashing colleague Linzi Harvey) presenting her dead Romans to the Nordic Medical Congress, but through the magic of pre-preparedness (and the internet) I bring to you today’s interview with Lauren McIntyre!

Lauren McIntyre is a PhD Candidate in Osteoarchaeology at the University of Sheffield. Her PhD project is focussed on reconstructing the population of Roman York using osteological evidence. Lauren is also Associate Osteologist for On Site Archaeology.

AA: So, tell me a little bit about your work:

LM: For my PhD project I’ve collected osteological data from as many skeletons dating to the Roman occupation of York as I could get my hands on! I’ve ended up with information for nearly 800 individuals from about a 340 year time span. For each individual I collected data on their age at death, sex, and living stature (height). I’ve used this information to look at the composition of the population, so I’ve been able to work out things like average life expectancy and the ratio of men to women present. I’ve also recorded every single example of dental or skeletal pathology. I’ve used this information to try and work out how healthy people were (what types of diseases or health problems people were likely to have), and to try and work out the types of foods people were eating.

AA: Wow, that sounds like a lot of work! Before you started your PhD was there much known about these things for Roman York or even Roman Britain?

LM: Some work has been done on a couple of different assemblages from Roman York (such as Trentholme Drive and Driffield Terrace), but no-one had ever looked at the town as a whole. The same is pretty much true for the rest of Roman Britain – there is plenty of work done for individual sites and cemeteries, but it’s very unusual to look at an entire settlement. What people forget is that a lot of burials are found on tiny archaeological sites – these may be isolated burials or just very small excavations where only a tiny piece of land is being excavated. Once you add these burials up for the whole town there can actually be quite a substantial number, which could contribute significantly to the story of the population.

AA: Can you tell us a little bit about Roman York before we get on to exactly what you’ve discovered?

LM: York is thought to have been founded in 71AD by the 9th Roman Legion. It was originally established as a fortress as part of the Roman expansion into the north of England and Scotland. A civilian settlement eventually grew up around the fortress and it became an important urban centre. By the third century York was made an official Roman colony and shortly after it was made the Roman capital of the north of Britain. It would have been quite a cosmopolitan town. There’s lots of evidence for trade with other parts of the Roman Empire – for example we know they were importing wine from the Rhone valley and olive oil from Spain, as well as other exotic foods like figs and grapes. There’s a lot of evidence for North African communities living in the town, which may be linked to the arrival of the 6th Legion in the second century, but also with the arrival of Emperor Septimus Severus who was born in an area that’s now in modern day Libya. So there could have been people from all different parts of the Roman Empire living in York as well as those who were born more locally.

AA: Wow, so York sounds like it was a pretty happening place back in the day! With information on that many hundreds of people you must have found some interesting things. What are some of the population-wide characteristics you’ve noticed – and have you found any interesting individuals that stand out from the crowd?

LM: Well, I’ve found that there are significantly more men living in the town than women. This is probably to be expected – after all, we know the town was a military installation. What’s interesting is that adult life expectancy in the town is approximately equal between men and women. Most other Romano-British urban sites have elevated male life expectancy. I’ve found that approximately equal life expectancy is more likely to be found at sites with a large military presence (the same thing was true at Gloucester, Colchester and London). This is probably because men working in the military were more likely to die at a younger age, which makes their overall adult life expectancy much closer to the female estimates.

As for interesting individuals, there are quite a few! One individual is a lady of north African descent, who was buried on the north west side of York. This lady is quite young, probably only in her late teens or early twenties. She also has lots of interesting grave goods such as a mirror and gold jewellery, suggesting she was quite wealthy. She’s known as the Ivory Bangle Lady (because of the ivory bangle she was buried with) and she’s currently on display in the Yorkshire Museum.

AA: It seems like interpretation plays a big part in understanding your data. With the example you gave of the life expectancies, how do you know it is the men dying at a younger age, instead of the women dying at an older age? Is there some sort of ‘Roman census’ that you can compare your site against?

LM: For each skeleton I examined, I worked out the approximate age they were at when they died. This is done by looking at certain parts of certain bones, for example the auricular surface of the pelvis, and attributing the person a rough age at death based on the appearance of the area you’re looking at. Once I put all the male and female ages together I applied different mathematical techniques to work out average life expectancy at birth, average adult life expectancy and so on. When I compared my results to studies that used similar methods, the general trend across Romano-British sites suggests that men were more likely to live a few years longer than women in the same populations. Unfortunately there isn’t any Roman census data for Britain that I could use for comparison, although I am about to have a look at some demographic work done using census data from Roman Egypt.

AA: Okay, I have to ask: how do you know she is north African? And do you have any pictures you could show us?

LM: A study published in Antiquity (by Leach et al., article no. 84: 131-145) in 2010 showed how analysis of stable isotopes found in the skeleton’s tooth enamel suggested that the skeleton was of a non-local origin. This individual most probably grew up in Western Europe or somewhere in the Mediterranean. The observed craniometric characteristics were found to be mixed, in that the individual’s skull comprised only a few characteristics commonly found in white European populations, instead having more in common with characteristics found in African-American populations. I should stress that this type of analysis cannot give us a specific region of origin for this individual, but it is highly likely, given the context, that the observed affinity with the African-American reference population is the result of mixed ancestry. There is already a lot of archaeological evidence (from pottery, historical documents etc) that there were individuals of North African origin living in York during the Roman period, and populations in Roman North Africa are well known epigraphically for being very mixed, comprising Mediterranean, Phoenician and Berber groups to name but a few. When you put all the evidence together, it’s likely that even if she wasn’t born in North Africa, she probably had descendants who were.

This is only a brief summary of the findings, and I unfortunately I don’t have any pictures I can share. If anyone’s really interested in the study I suggest they look up the full article. Ancestry studies have come under fire a lot in the past, because craniometric techniques in particular have been used to come up with some fairly dodgy and even racist notions about various geographical groups. The Ivory Bangle Lady study is a very good example of how identification of ancestry and geographical origins can be investigated thoroughly and successfully using a multidisciplinary approach.

AA: Wow, it really makes you think more about what Roman York would have been like and the different types of people that would have been a part of it. It’s also really refreshing to see lots of different methods being used to reach the same conclusion. It makes for a pretty convincing case!

It has been great learning about your research – and about Roman Britain in general – thanks so much for taking the time to share it with us.

LM: Thanks for reading!

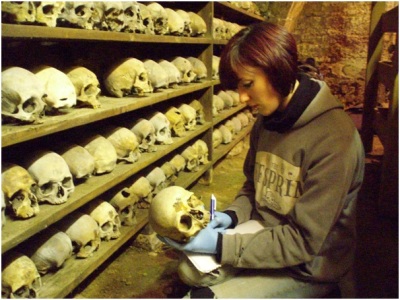

Lauren examining skeletal remains at the Rothwell charnel chapel.

Lauren McIntyre is a PhD Candidate in Osteoarchaeology at the University of Sheffield. Her PhD project is focussed on reconstructing the population of Roman York using osteological evidence. If you’re interested in learning more about Lauren and her research, you can visit her University profile and her Academia profile. Lauren is also a part of the current research team offering one-day and five-day short courses in Human Osteology at the University of Sheffield.

*The answer is: A lot. But sadly one thing they did not do for us, was discover coffee (as far as we know).

Leach, S., Eckardt, H., Chenery, C., Muldner, G., & Lewis, M. (2010). A Lady of York: migration, ethnicity and identity in Roman Antiquity, 84 (323), 131-145